Adoptive Children Resemble Adoptive Family Through Enviormental Factors

Abstract

Background

After adoption, children exposed to institutionalized care prove meaning improvement, just incomplete recovery of growth and developmental milestones. There is a paucity of information regarding risk and protective factors in children adopted from institutionalized care. This prospective study followed children recently adopted from institutionalized care to investigate the relationship betwixt family environs, executive function, and behavioral outcomes.

Methods

Anthropometric measurements, physical exam, endocrine and bone historic period evaluations, neurocognitive testing, and behavioral questionnaires were evaluated over a 2-year menses with children adopted from institutionalized intendance and non-adopted controls.

Results

Adopted children had significant deficits in growth, cognitive, and developmental measurements compared to controls that improved; notwithstanding, residual deficits remained. Family cohesiveness and expressiveness were protective influences, associated with less behavioral problems, while family conflict and greater accent on rules were associated with greater risk for executive dysfunction.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that a cohesive and expressive family surroundings chastened the event of pre-adoption adversity on cognitive and behavioral evolution in toddlers, while family conflict and greater emphasis on rules were associated with greater risk for executive dysfunction. Early assessment of child temperament and parenting context may serve to optimize the fit between parenting fashion, family unit environment, and the child'due south development.

Impact

-

Children who experience institutionalized care are at increased risk for significant deficits in developmental, cognitive, and social functioning associated with a disruption in the development of the prefrontal cortex. Aspects of the family caregiving environment moderate the effect of early life social deprivation in children.

-

Family unit cohesiveness and expressiveness were protective influences, while family unit conflict and greater accent on rules were associated with a greater gamble for executive dysfunction problems.

-

This study should be viewed every bit preliminary data to be referenced past larger studies investigating developmental and behavioral outcomes of children adopted from institutional care.

Introduction

The scientific discipline of early childhood development is clear well-nigh the importance of early experiences, caregiving environment, and environmental threats on biological, cognitive, and behavioral development. Immature children exposed to institutionalized care, which oftentimes corresponds with social deprivation and low caregiving quality, accept an increased risk for behavioral problems and psychopathology.i,2,3,four,5,vi Intervention studies of children who experienced institutionalized care and are later adopted or placed into foster care provide evidence that a more favorable caregiving environment may lead to improved outcomes in growth, wellness, and development, and an overall reduced risk for psychopathologyseven,8,ix,10,xi and may reverse the negative furnishings of early deprivation on hypothalamic pituitary axis operation and neurobehavioral development.8,12,13,14,fifteen,16,17,18,19,20

Prior studies have addressed the furnishings of institutionalized intendance on neurodevelopment and identified significant deficits in cognitive and social performance, and developmental delay in children adopted post institutionalization.3,5,6,8,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 Age at adoption and fourth dimension spent in institutionalization are associated with significant and oftentimes detrimental furnishings on overall outcomes.21,22 Institutionalized care and accompanying stimulus impecuniousness affect the development of the prefrontal cortex.23,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 The prefrontal cortex has a key part in the development and regulation of executive functions as well equally the control of the autonomic system residue. Executive functions refer to a group of higher-order cognitive processes that coordinate the planning and execution of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, likewise as the storage of information in working memory.36,37,38,39 Executive skills are critical building blocks for the early on development of cognitive and social capabilities; the gradual conquering of these skills stand for to the development of the prefrontal cortex and other brain areas from infancy to adulthood.36,37,38,39

In that location is a paucity of research about mail service-adoption parenting styles that may promote recovery in children later institutionalized care. Aplenty evidence supports that the early caregiving environment is a consistent predictor of developmental outcomes and executive skills.40,41,42,43,44 The developing executive role system is influenced by a kid's experiences, response to stress, and structural and molecular changes associated with changes in the hormonal milieu in the encephalon during sensitive periods of development. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) has a critical part in human brain development and cognition likely due to the furnishings of this steroid in enhancing brain plasticity.45,46 Results of recent studies advise that DHEA affects the evolution of cortico-amygdala46 and cortico-hippocampal functions47 that are important to encoding and processing of emotional, spatial, and social cues, too every bit attention and working memory processes. In addition, steroids that are DHEA precursors, such as progesterone and allopregnanolone, have disquisitional roles in neuroprotection.36,37,38,39

In this prospective study, we followed the development of children who experienced institutionalized care 2 years post adoption by a family in the United states. We examined the relationship between family environment, growth, endocrine and levels of neurosteroids, executive performance, and cognitive development in children adopted from institutionalized intendance and non-adopted controls to place factors related to developmental recovery and behavioral outcomes.

Methods

Participants

We recruited children adopted from institutionalized intendance in Eastern Europe within ii months of adoption by a US family. Eligible participants had no history of pregnant medical, developmental, or behavioral problems. Participants were screened to determine that they spent at to the lowest degree 8 months in the institution/orphanage setting and were placed in the establishment/orphanage at 6 months of age or less. Participants were recruited from local adoption referral centers. Kid participants were recruited for a command group and were cohort age–sex-matched with the adopted subjects. The controls were good for you children with no history of significant medical, psychological, or behavioral disorders. Exclusion criteria for the study included documented history of growth hormone deficiency, history of chronic affliction (i.east., renal failure, chronic lung affliction, diabetes, hypothyroidism, chromosomal abnormalities, medical weather condition known to be associated with developmental delay (i.e., fetal booze syndrome (subjects were screened using criteria developed by Hoyme et al.48)) chronic communicable diseases (e.g., AIDS, hepatitis), or precocious puberty. Socio-economic scores were similar between groups.

Participants were seen at baseline (within 2 months of arrival in the United States for adopted subjects) at 1- and two-twelvemonth follow-up. All studies were conducted under protocol 06-CH-0223 that was approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Plant of Kid Wellness and Homo Development Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian. A total of 11 adopted children and 27 controls were recruited. X adopted children and 19 controls completed at least ii follow-upwards visits and were included in the assay. The written report was airtight to recruitment earlier than predictable due to the intermission of adoptions from Eastern Europe to the U.s.a..

Measures

Anthropometric measurements, physical examination, neurocognitive testing, behavioral questionnaires, and endocrine labs and os age (adopted children just) were evaluated over a 2-twelvemonth period. Anthropometric measures included meridian, weight, body mass index (BMI), mid-arm circumference (MAC), triceps skinfold (TSF), subscapular skinfold (SSF), waist circumference (WC), and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) by a registered dietitian.

Due to the participants' age and upstanding issues related to procedures that betrayal good for you child participants to chance, blood and bone age x-rays to assess nutritional and endocrine condition were obtained for adopted children but (forth with clinically indicated laboratory tests). Serum cortisol, DHEA, testosterone, estradiol, and serum neurosteroid profile were also collected (convenience sample: between 11 a.m. and ane p.m.).

Neurocognitive testing was performed by a pediatric neuropsychologist and included either the Bayley III or Differential Abilities Scale II (DAS) based on age-appropriate guidelines. Behavioral questionnaires included Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function- Preschool (Cursory-P), Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA), Colorado Child Temperament Inventory (CCTI), and Family Surroundings Scale (FES). Waters Zipper Beliefs Q-sort (AQS) assessment of child attachment (Waters, SUNY) was performed by two trained observers at the initial visit.

The Bayley III is a clinical evaluation by a trained clinician to identify developmental issues in infants and toddlers and consists of the following domains, adaptive behavior, noesis, language, motor skills, and social–emotional capacities. Mean scores for scales are x, with an SD of three.49 The DAS is a nationally normed (Us) battery of cognitive and achievement tests for children anile two years 6 months to 17 years eleven months beyond a range of developmental levels; hateful is 100, SD of 15.l The CBCL questionnaire is a validated parent-written report measure out to assess emotional (internalizing and externalizing symptoms) and maladaptive behavior in children.27 The Brief-P is a reliable, valid parent-report inventory to assess executive part in preschool children; our assay focused on the clinical scales of: inhibit (control behavioral response), shift (ability to alternate attending), emotional command (regulate emotional responses), working memory (ability to concur information when completing a job), plan/arrangement (to plan, organize), and Global Executive Composite (GEC). Scores on the CBCL and BRIEF-P are normalized to a mean of 50 (SD ten), with college scores indicative of greater degrees of dysfunction and scores >65 considered to be clinically significant.51 ITSEA is a validated measure completed by the parent to assess social–emotional problems and competence in children (1–3 years of age) and is comprised of four domains, externalizing (impulsive, aggression), internalizing (low, anxiety, separation distress, inhibition to novelty), dysregulation (sleep issues, negative emotions, sensory sensitivity), and competence (attention, compliance, play, mastery, empathy, prosocial peer relations).52

The CCTI is a validated inventory designed to assess the temperament of children by parental study.53 The FES is a self-reported questionnaire to assess social climate and ecology family unit characteristics and family functioning and emotions. The FES is categorized into three domains with x subscales—relationship dimensions (cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict), personal growth dimensions (independence, achievement orientation, intellectual–cultural orientation, active–recreational orientation, and moral–religious aspect), and arrangement maintenance dimensions (organization and control).54 The AQS is widely used to appraise child zipper behavior and is based on Ainsworth'south study of secure attachment behavior in infants. The AQS assesses the correlation between secure attachment blazon and child–parent boundaries and has high validity. The AQS security score is the correlation of a specific child's Q-sort to prototypical secure kid and the score range is from −1.0 to +1.0.55,56

We hypothesized that aspects of the family unit surround, equally measured by FES, would be associated with outcome measures of cognitive, executive function, and behavioral problems.

Statistical analysis

To compare children of different ages, anthropometric measurements, and cognitive function scores were converted to z-scores (the departure between the kid's measurement/score and the age mean or the hateful provided by standardized cognitive exam, divided by the standard deviation (SD)). For length, height, weight, BMI, OFC, MAC, TSF, SSF, and WC z-scores were calculated using the plan PediTools,57 based on ways for historic period and SDs obtained past the National Wellness and Nutrition Exam Survey (Heart for Disease Command and Prevention (CDC)). The CDC provides a ready of growth measurements that are standardized amid an ethnically diverse population.

Descriptive statistics were examined, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to evaluate grouping differences in growth, cerebral, and behavior problems. Statistical comparisons included paired t tests, ANOVAs, correlation, and regression analysis. Regression analyses were conducted to examine which aspects of the family environment predicted cerebral or behavioral result measures. Analyses were conducted using the SPSS software. A p value <0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

Results

Subjects

There was no significant age or sex activity deviation between adopted and control groups at the initial visit (adopted: 27.5 ± 9.3 months (range 14–xl months), 6 females, 4 males; control: 30.seven ± fourteen months (range 10–58 months), 9 females, 10 males). For adopted subjects, the average time spent in institutionalized care was 23.6 ± 9 months. All the adopted children in our study were engaged with early intervention educational services.

Growth

At baseline, adopted subjects had significantly lower z-scores for height/length, weight, OFC, and MAC compared to controls (p < 0.5). At baseline, one adopted discipline had acme and weight z-score <2 SD, compared to one subject in the control group with weight <2 SD; half dozen adopted subjects had OFC <ii SD compared to one control subject with OFC <two SD. No pregnant differences were plant for z-scores for TSF or SSF or WC. At ii-yr follow-up, adopted subjects showed pregnant comeback in z-scores of elevation and weight; at that place were no differences between the two groups for anthropometric measures. For adopted subjects at follow-upwards, 1 child had weight SD < ii SD and four children had OFC < two SD. OFC was not obtained in most control subjects at 2-yr follow-up. (Table 1).

Endocrine and metabolic measures (adopted children)

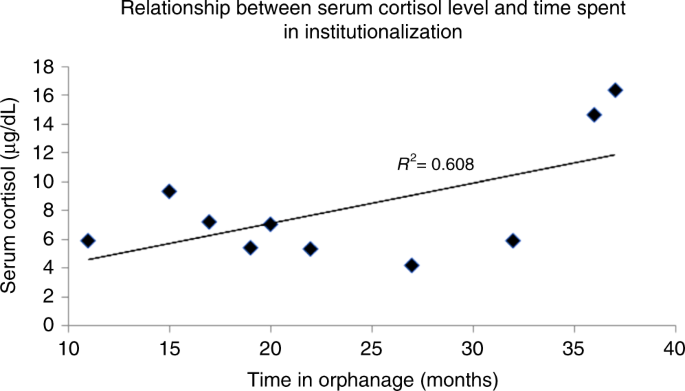

Serum cortisol was obtained betwixt 11 a.thou. and 1 p.1000. The range of cortisol levels was 4.two to 16.3 μg/dL. Fourth dimension in orphanage care was positively associated with serum cortisol at baseline (R ii = 0.61, p < 0.06) (Fig. 1). Due to the small sample size, the ii outliers with longer time in orphanage care may have skewed the results; however, serum cortisol levels at follow-upward were non statistically different from baseline values. We planned to collect salivary cortisol levels (diurnal) for both adopted and control subjects; however, due to poor compliance or lack of ample quantity of sample nerveless, in that location was insufficient information for assay. At baseline, thyroid function results were within normal limits, except for ane kid who had mildly elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone with normal gratuitous T4, which normalized at follow-up visit. Other endocrine hormone levels were within normal limits for age/sex. Insulin-similar growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) z-scores at baseline (0.62 ± 0.2, 1.2 ± 0.iii, respectively) and follow-up (0.43 ± 0.3, 1.58 ± 0.3, respectively) were within normal range. Growth factors were not a predictor of cognitive outcome. At the initial visit, bone historic period was consistent with chronological age in five children, advanced in three children, and delayed in ii children. At follow-up, bone age was consequent with chronological age in six, advanced in two, and delayed in two children.

Cortisol levels in adopted children: fourth dimension in orphanage care is positively correlated with serum cortisol at baseline (r 2 = 0.608, p < 0.06). Serum cortisol was obtained between xi am and 1 pm. (convenience sample). Cortisol levels ranged from 4.two to 16.3 μg/dL.

A serum lipid panel was obtained (convenience sample, non-fasting). At baseline, serum cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels were inside normal limits for age. Serum high-density lipoprotein levels were <forty mg/dL in six of the ten subjects, and at follow-upwardly remained <40 mg/dL in 2 of the nine subjects.

Serum neurosteroids were measured at baseline (northward = half-dozen) and follow-up (n = ix) by isotope dilution high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.58 Allopregnanolone levels were within the expected range for the assay and levels were similar to a recent study in a salubrious population of toddlers that found no significant diurnal variation, as well as no differences between males and females, in the first iii years of life.59 Serum tetrahydro-11 deoxycortisol, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone, and DHEA levels were at the lower limit of detection for the analysis and did not modify in the six subjects who had both baseline and follow-up measured (Table 2).

Cognitive data

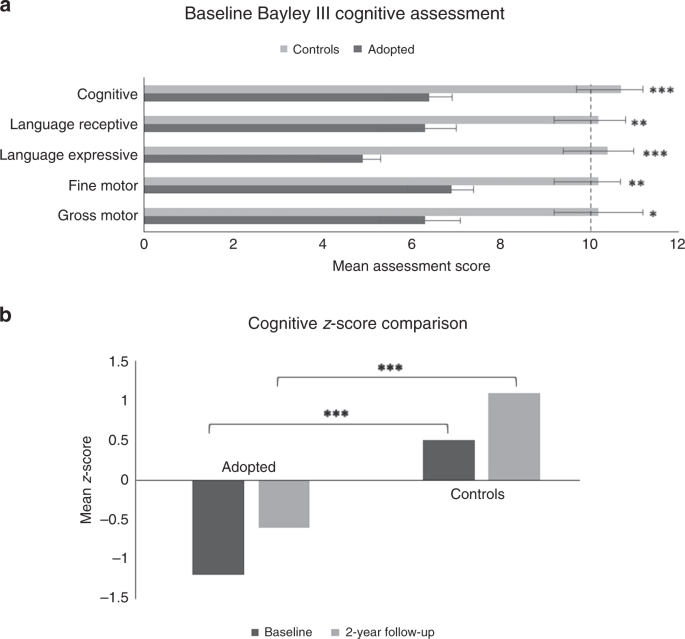

At baseline, adopted subjects had significantly lower scores compared to controls on all cognitive measures (Bayley III): cerebral, language receptive, linguistic communication expressive, fine motor, and gross motor (due north = 9 of adopted and 10 of controls were historic period appropriate for testing with Bayley 3). To compare changes in scores from baseline to follow-up, overall cognitive z-scores were calculated (z-score of Bayley III or DAS General Cognitive Ability) and ANOVA analysis was performed. At baseline, general cerebral z-scores were significantly lower for adopted vs. controls; at ii-year follow-up, there was a trend for comeback in scores for adopted; withal, residual differences remained compared to controls. For adopted subjects, lower OFC z-scores (baseline) were associated with lower cerebral scores at follow-upward (Tabular array 3 and Fig. 2).

a Comparison of mean scores on Bayley Iii at baseline. Adopted subjects had significantly lower scores in all subscales compared to controls. b Comparison of baseline and follow-up cognitive z-scores. Adopted subjects had significantly lower z-scores at baseline and although a trend was noted for improvement in adopted subjects' scores from baseline to follow-upward, residual differences remained. Error bars indicate standard error. *P < 0.05.

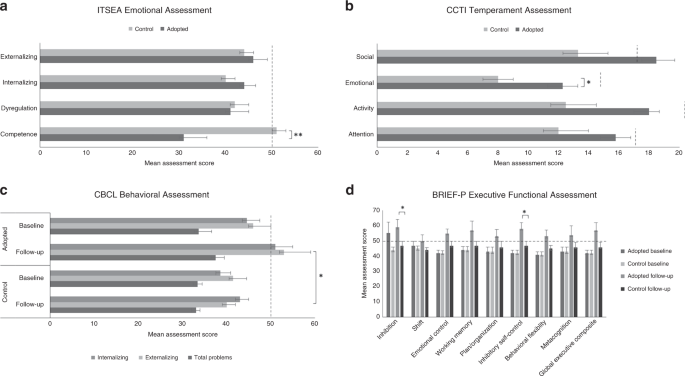

Behavioral data

At baseline, adopted children had significantly lower scores than controls for the ITSEA competence subscale (p < 0.001; F = 19.017); lower scores are associated with lower social–emotional competence. Since almost subjects were to a higher place the age limit for use of ITSEA at follow-up, these data were not included in the analysis. At baseline, adopted children had significantly higher scores on the emotional subscale of the CCTI compared to controls (p < 0.03; F = 5.516). Baseline CBCL results showed no deviation between the adopted and control group for whatever subscale scores. At two-year follow-upwards, adopted children had significantly higher scores on externalizing symptom subscales compared to controls (p < 0.03; F = v.251).

For adopted subjects at baseline, parent responses for the BRIEF endorsed clinically significant inhibitory control in one-half the children (p < 0.05; F = 4.424); no meaning difference was found between the adopted and control groups for other subscales. At follow-up the adopted group had significantly college scores (college scores associated with more than problems) compared to controls for the following subscales: inhibition (p < 0.04; F = five.027), inhibitory self-control (p < 0.03; F = v.328), with a trend noted for working retentiveness and GEC (Fig. 3).

Comparison of mean scores on a ITSEA-Emotional Assessment (baseline); b CCTI-Temperament Assessment (baseline); c CBCL-Behavioral Cess (baseline and follow-upward); and d BRIEF-P-Executive Role (baseline and follow-up) of adopted vs. controls. Mistake bars indicate standard error. *P < 0.05.

Waters Q attachment scores showed no difference in attachment between adopted children and controls; AQS scores strongly correlated with norms for a sensitive response. Based on that, nosotros concluded that there were no differences between parents' sensitivity and kid zipper in either group and their secure–insecure zipper distribution was comparable with that of normative groups (information not shown). FES scores at baseline showed a significant difference for just the independence subscale score between adopted vs. command groups (p < 0.05; F = 4.418).

To identify sociodemographic and family surround factors associated with increased take a chance for executive dysfunction or behavioral bug, a correlational analysis was performed betwixt demographic variables of kid gender and age and executive function variables to determine possible covariate variables. Sex was not significantly correlated with any executive function variables and therefore non included in any future analysis. Even so, age at baseline was significantly correlated with BRIEF subscales; correlation and linear regression analyses were used for these executive function variables.

For adopted subjects, the baseline FES subscales control and conflict were predictors of college GEC scores at follow-up (Cursory measure; higher scores associated with dysfunction) (R ii = 0.91; F = 14.48, p = 0.03). FES subscale achievement positively correlated with modify in cognitive z-scores (R 2 = 0.433; F = six.106, p = 0.04). FES subscales cohesion and expressiveness were negatively associated with a alter in internalizing scores of CBCL (R 2 = −0.9; p = 0.04), that is, greater cohesion and expressiveness were associated with lower scores on internalizing symptoms of CBCL. FES subscale control was a predictor of a higher internalizing score (CBCL) at follow-up (R two = 0.74; F = 10.893, p = 0.03); greater emphasis on rules and procedures were associated with more than internalizing symptoms, which is a reflection of mood disturbance (i.due east., anxiety, depression, social withdrawal). CCTI emotionality was associated with an increment in externalizing scores of CBCL for adopted subjects (R ii = 0.97; p < 0.005) (Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

This prospective written report followed the development of children adopted from institutionalized care for 2 years mail adoption compared to controls. Broadly, our findings are consequent with the literature, showing significant but not consummate growth and developmental recovery mail service adoption for children exposed to institutionalized intendance. Kroupina et al.28 reported that growth factors (IGFBP3) at baseline were a negative predictor and modify of head circumference and cognitive scores at 6 months were positive predictors, of cognitive outcomes at 30 months post adoption. Our data did not bear witness a correlation between baseline growth cistron z-scores and cognitive outcome at follow-upwardly, perhaps due to the constraints of our small sample size. However, OFC z-scores at baseline were a predictor of cognitive scores at 2-year follow-up. Also, Kroupina et al.28 reported that smaller stature at baseline and weight gain were associated with improved height event at 30- month follow-up, and younger age and lower weight at baseline were a predictor of better catch-up growth. Our data did not replicate the findings of Kroupina et al.28 regarding predictors of catch-up growth, likely due to the constraints of our sample size. Baseline z-scores for tiptop, weight, and OFC were similar between our study and Kroupina et al.,28 which had a larger sample size. As expected, there was a negative correlation between time in orphanage intendance and baseline summit and weight z-scores. Consequent with previous studies,viii,21,24,26,34,threescore,61,62,63,64 our results support specific aspects of the family surround that are associated with executive function and behavioral symptomology 2 years subsequently adoption.65,66 Specifically, greater conflict and less flexible rules in a family were predictors of higher scores of global executive dysfunction. Cursory scores reflect the parent's observations of the child's everyday executive performance relative to the parent's expectations (not an accented level of performance) and thus serve as a screening tool for executive dysfunction. Also, in this study, adopted children were found to have higher scores for behavioral inhibition, an aspect of temperament characterized as social reticence that is reported to be stable across babyhood and is associated with greater risk for developing social withdrawal, anxiety disorders, and internalizing problems. Prior studies written report that developmental outcomes associated with behavioral inhibition can be influenced by the caregiving context; authoritarian mode (i.east., lack of emotional warmth, non-transparent annunciation of rules, and high levels of command) is detrimental for social developmental outcomes.67

Family cohesion and expressiveness were a protective influence; at 2-twelvemonth follow-up, stronger family cohesion and expressiveness were associated with lower internalizing scores (i.east., less problems with mood disturbance, including anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal). Prior studies of internationally adopted children reported either higher mean internalizing symptoms or no differences in internalizing scores between adopted vs. non-adopted children.66,68,69 Consistent with prior studies, nosotros found higher externalizing scores (i.eastward., greater problems with assailment, conflict, and violation of social norms) on the CBCL at two-twelvemonth follow-up for adopted children that were associated with higher emotionality scores on CCTI.70 Scores on the FES at baseline did not differ significantly betwixt groups, suggesting that there were no differences in perceived family characteristics between adopted and controls.54

Every bit expected, at baseline visit at that place were significant differences in measures of cognitive function betwixt adopted children and controls; overall mean scores improved but remained lower than controls at 2-twelvemonth follow-up. Cognitive scores were negatively associated with OFC z-scores (baseline visit). At baseline, compared to controls, adopted children scored lower on measures of competence (every bit measured by ITSEA) and scored higher (associated with more than problems) on measures of emotionality (as measured by CCTI) and inhibitory control (as measured by BRIEF). At follow-up, adopted children scored higher (associated with more problems) on measures of externalizing symptoms, inhibition, inhibitory self-command, behavioral flexibility, working memory, and GEC (BRIEF). The developing executive function system is influenced past a child'due south experiences and response to stress, which impacts the developing prefrontal cortex. In this written report, although the measurement of neurosteroids did not reveal any relationship to measures of cerebral or behavioral symptomology; the small sample size and lack of data in the command grouping limit estimation and future inquiry is warranted.

We did not identify differences in attachment measures in adopted vs. controls. We observed "indiscriminate friendliness" in many of the adopted subjects, as has been described in the literature.5,63 Our observations are consistent with prior studies that note indiscriminate sociability in children with secure zipper.71,72

The strengths of this study are the prospective blueprint and the differentiation of behavioral issues noted at adoption placement versus those that manifest later. Limitations of the study include the small number of participants (the study was terminated prematurely due to the cessation of adoptions from East Europe). Another limitation was that measures of internalizing, externalizing behaviors, and executive office included just parental assessments of behavior. Also, the lack of salivary cortisol data (due to either inadequate quantity of samples nerveless or poor compliance with collection in this infant/toddler population) is regrettable since salivary cortisol levels are widely used and are an invaluable tool for pediatric studies and would take provided useful data for comparison of adopted and control subjects.

This report, in the context of a small sample size, should exist viewed as a pilot report in the field of developmental pediatrics. Here we find that specific aspects of the family caregiving environs moderate the effects of social impecuniousness during early childhood on executive function and behavioral issues. These findings provide preliminary data for larger studies that volition farther investigate the developmental furnishings that manifest in institutionalized children.

Conclusion

In summary, findings from this written report support a cohesive and expressive family environment moderated the result of prior pre-adoption adversity on cognitive and behavioral development in toddlers. Family conflict and greater emphasis on rules/procedures were associated with a greater risk for behavioral problems at two-year follow-up. Early on assessment of child temperament kid and parenting context may provide useful data to optimize the fit between parenting style, family unit environs structure, and the kid'due south development.

References

-

Harlow, H. F. Total social isolation: furnishings on macaque monkey behavior. Science 148, 666 (1965).

-

Heim, C. & Nemeroff, C. B. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol. Psychiatry 49, 1023–1039 (2001).

-

Gunnar, M. R. & van Dulmen, Thou. H., International Adoption Project T. Behavior problems in postinstitutionalized internationally adopted children. Dev. Psychopathol. 19, 129–148 (2007).

-

Smyke, A. T., Dumitrescu, A. & Zeanah, C. H. Attachment disturbances in young children. I: the continuum of caretaking prey. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 41, 972–982 (2002).

-

Tizard, B. & Rees, J. The outcome of early institutional rearing on the behaviour bug and affectional relationships of four-year-old children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 16, 61–73 (1975).

-

Rutter, Yard. et al. Early adolescent outcomes of institutionally deprived and non-deprived adoptees. III. Quasi-autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 1200–1207 (2007).

-

Hellerstedt, W. L. et al. The International Adoption Project: population-based surveillance of Minnesota parents who adopted children internationally. Matern. Kid Wellness J. 12, 162–171 (2008).

-

Kroupina, M. K. et al. Adoption as an intervention for institutionally reared children: HPA functioning and developmental status. Infant Behav. Dev. 35, 829–837 (2012).

-

O'Connor, T. Thousand. Early experiences and psychological evolution: conceptual questions, empirical illustrations, and implications for intervention. Dev. Psychopathol. fifteen, 671–690 (2003).

-

Rutter, M. et al. Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: disinhibited attachment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 17–thirty (2007).

-

Weitzman, C. & Albers, L. Long-term developmental, behavioral, and zipper outcomes afterward international adoption. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 52, 1395–1419 (2005).

-

De Kloet, E. R., Vreugdenhil, East., Oitzl, M. S. & Joels, M. Encephalon corticosteroid receptor rest in health and disease. Endocr. Rev. 19, 269–301 (1998).

-

Heim, C., Plotsky, P. 1000. & Nemeroff, C. B. Importance of studying the contributions of early on agin experience to neurobiological findings in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 641–648 (2004).

-

Suomi, S. J., Delizio, R. & Harlow, H. F. Social rehabilitation of separation-induced depressive disorders in monkeys. Am. J. Psychiatry 133, 1279–1285 (1976).

-

Meaney, M. J. Maternal care, cistron expression, and the manual of individual differences in stress reactivity beyond generations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1161–1192 (2001).

-

Imanaka, A. et al. Neonatal tactile stimulation reverses the result of neonatal isolation on open-field and anxiety-like behavior, and pain sensitivity in male person and female adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav. Brain Res. 186, 91–97 (2008).

-

Holmes, A. et al. Early life genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 29, 1335–1346 (2005).

-

Brand, A. E. & Brinich, P. M. Behavior problems and mental health contacts in adopted, foster, and nonadopted children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 40, 1221–1229 (1999).

-

Leve, Fifty. D., Fisher, P. A. & Chamberlain, P. Multidimensional treatment foster care as a preventive intervention to promote resiliency amid youth in the kid welfare system. J. Pers. 77, 1869–1902 (2009).

-

Fox, N. A. et al. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cerebral development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. J. Kid Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 919–928 (2011).

-

Johnson, D. E. Adoption and the result on children's development. Early on Hum. Dev. 68, 39–54 (2002).

-

Beckett, C. et al. Behavior patterns associated with institutional deprivation: a written report of children adopted from Romania. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 23, 297–303 (2002).

-

Danese, A. & McEwen, B. Due south. Adverse babyhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 106, 29–39 (2012).

-

Estimate, South. Developmental recovery and deficit in children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 34, 49–62 (2003).

-

Kaler, S. R. & Freeman, B. J. Assay of environmental impecuniousness: cerebral and social development in Romanaian orphans. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 35, 769–781 (1994).

-

Miller, Fifty. C., Kiernan, Thousand. T., Mathers, M. I. & Klein-Gitelman, M. Developmental and nutritional status of internationally adopted children. Curvation. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 149, xl–44 (1995).

-

Achenbach, T. G. & Rescorla, L. A. Transmission for the AESBA Schoolhouse-Age Forms and Profiles (Research Middle for Children, Youth, and Families, Academy of Vermont, Burlington, 2001).

-

Kroupina, M. G. et al. Associations between physical growth and general cerebral functioning in international adoptees from Eastern Europe at 30 months mail-inflow. J. Neurodev. Disord. 7, 36 (2015).

-

Fishbein, D. H. et al. Mediators of the stress-substance-utilize human relationship in urban male person adolescents. Prev. Sci. 7, 113–126 (2006).

-

Arnsten, A. F. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 410–422 (2009).

-

Ohta, K. I. et al. The effects of early life stress on the excitatory/inhibitory residue of the medial prefrontal cortex. Behav. Brain Res. 379, 112306 (2020).

-

Pena, C. J., Nestler, E. J. & Bagot, R. C. Environmental programming of susceptibility and resilience to stress in adulthood in male mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13, forty (2019).

-

Callaghan, B. Fifty., Sullivan, R. Yard., Howell, B. & Tottenham, N. The international club for developmental psychobiology Sackler symposium: early arduousness and the maturation of emotion circuits–a cross-species assay. Dev. Psychobiol. 56, 1635–1650 (2014).

-

Bos, Grand. J., Pull a fast one on, N., Zeanah, C. H. & Nelson Iii, C. A. Effects of early on psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive function. Front. Behav. Neurosci. three, sixteen (2009).

-

Liston, C., McEwen, B. S. & Casey, B. J. Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.s. 106, 912–917 (2009).

-

Shaw, P. et al. Intellectual power and cortical evolution in children and adolescents. Nature 440, 676–679 (2006).

-

Lenroot, R. K. et al. Differences in genetic and environmental influences on the human cerebral cortex associated with evolution during childhood and adolescence. Hum. Encephalon Mapp. 30, 163–174 (2009).

-

Tsujimoto, S. The prefrontal cortex: functional neural development during early childhood. Neuroscientist fourteen, 345–358 (2008).

-

IoMaNR Council. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (The National Academies Printing, Washington, 2000).

-

Dowsett, S. 1000. & Livesey, D. J. The development of inhibitory control in preschool children: effects of "executive skills" training. Dev. Psychobiol. 36, 161–174 (2000).

-

Bell, M. A. & Wolfe, C. D. Emotion and knowledge: an intricately bound developmental process. Child Dev. 75, 366–370 (2004).

-

Wolfe, C. D. & Bong, One thousand. A. Working memory and inhibitory control in early childhood: Contributions from physiology, temperament, and language. Dev. Psychobiol. 44, 68–83 (2004).

-

EKSNIoCHaH Development. The NICHD Written report of Early Kid Care and Youth Development (SECCYD): Findings for Children up to Historic period iv 1/2 Years (Government Printing Office, Washington, 2006).

-

Rhoades, B. 50., Greenberg, M. T., Lanza, S. T. & Blair, C. Demographic and familial predictors of early executive function evolution: contribution of a person-centered perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 108, 638–662 (2011).

-

Nguyen, T. V. et al. Interactive effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone on cortical thickness during early on brain development. J. Neurosci. 33, 10840–10848 (2013).

-

Nguyen, T. 5. et al. A testosterone-related structural brain phenotype predicts ambitious behavior from babyhood to machismo. Psychoneuroendocrinology 72, 219 (2016); erratum 63, 109–118 (2016).

-

Nguyen, T. 5. et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone impacts working retentiveness by shaping cortico-hippocampal structural covariance during development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 86, 110–121 (2017).

-

Hoyme, H. Due east. et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics 115, 39–47 (2005).

-

Bayley, Due north. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development: Administration Manual 3rd edn (Pearson Psychcorp, San Antonio, 2006).

-

Elliott, C. D., Salerno, J. D., Dumont, R. & Willis, J. O. The Differential Ability Scales—Second Edition: Contempory Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues (Guilford Press, 2018).

-

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C. & Kenworthy, L. Beliefs Rating Inventory of Executive Part. Preschool Edition (PAR Inc., Lutz, 2000).

-

Carter, A. S., Briggs-Gowan, 1000. J., Jones, S. One thousand. & Little, T. D. The Babe-Toddler Social and Emotional Cess (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J. Abnorm. Kid Psychol. 31, 495–514 (2003).

-

Rowe, D. C. & Plomin, R. Temperament in early on childhood. J. Pers. Assess. 41, 150–156 (1977).

-

Moos, R. H. & Moos, B. South. Family Environment Calibration Manual (Consulting Psychologist Press, Palo Alto, 1981).

-

Ainsworth, One thousand. D. Due south. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Report of the Foreign Situation (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1978).

-

Waters, E. D. K. Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 50, 41–65 (1985).

-

Chou, J. H., Roumiantsev, S. & Singh, R. PediTools Electronic Growth Chart Calculators: applications in clinical care, inquiry, and quality improvement. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16204 (2020).

-

Parikh, T. P. et al. Diurnal variation of steroid hormones and their reference intervals using mass spectrometric analysis. Endocr. Connect. vii, 1354–1361 (2018).

-

Fadalti, One thousand. et al. Changes of serum allopregnanolone levels in the offset 2 years of life and during pubertal development. Pediatr. Res. 46, 323–327 (1999).

-

McGuinness, T. K. & Dyer, J. G. International adoption equally a natural experiment. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 21, 276–288 (2006).

-

Albers, 50. H. et al. Health of children adopted from the onetime Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Comparison with preadoptive medical records. JAMA 278, 922–924 (1997).

-

Benoit, T. C., Jocelyn, L. J., Moddemann, D. Thou. & Embree, J. E. Romanian adoption. The Manitoba experience. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 150, 1278–1282 (1996).

-

Chisholm, K. A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child Dev. 69, 1092–1096 (1998).

-

Rutter, G., English and Romanaian Adoptees (ERA) Written report Team. Developmental take hold of-upwardly, and deficit, post-obit adoption after severe global early privation. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 39, 465–476 (1998).

-

Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van, I. M. H. The importance of parenting in the development of disorganized zipper: evidence from a preventive intervention study in adoptive families. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46, 263–274 (2005).

-

Schoemaker, N. G. et al. A meta-analytic review of parenting interventions in foster care and adoption. Dev Psychopathol. 46, 1–24 (2019).

-

Guyer, A. E. et al. Temperament and parenting styles in early childhood differentially influence neural response to peer evaluation in boyhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 863–874 (2015).

-

Hawk, B. N. et al. Caregiver sensitivity and consistency and children'south prior family experience as contexts for early development within institutions. Infant Ment. Health J. 39, 432–448 (2018).

-

McCall, R. B. et al. Early on caregiver-child interaction and children'due south development: lessons from the Petrograd-USA orphanage intervention research project. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 22, 208–224 (2019).

-

Juffer, F. & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: a meta-assay. JAMA 293, 2501–2515 (2005).

-

O'Connor, T. Chiliad. et al. Child-parent attachment post-obit early institutional deprivation. Dev. Psychopathol. 15, nineteen–38 (2003).

-

O'Connor, T. G. & Rutter, M., English and Romanaian Adoptees Study Squad. Attachment disorder behavior post-obit early severe deprivation: extension and longitudinal follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39, 703–712 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and their families for their participation in this study. Nosotros thank Dr. Patrick Mason (International Adoption Center, Fairfax, VA), Dr. Penny Drinking glass (CNMC), Dr. Sharon Singh (CNMC), Dr. Pedro Martinez (NIMH), Dr. Steven Soldin (NIH CC DLM), and Dr. Moommal Shaihh (NICHD) for their assist. We acknowledge the University of Nevada School of Medicine for support of Dr. Rescigno's elective rotation with NICHD/NIH. This written report was supported past NIH grant Z01-HD008920.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Chiliad.F.K.: conceptualized and designed the report, coordinated and supervised information collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. A.L. and J.M.: collected data and carried out the initial analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Grand.R.: assisted with the analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.A.S.: conceptualized and designed the report, and critically reviewed the manuscript for of import intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and concur to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent

Consent for participation in this report was obtained from the legal guardians of the participating children.

Additional information

Publisher'south notation Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the commodity'southward Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Artistic Eatables license and your intended utilize is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Keil, Thousand.F., Leahu, A., Rescigno, G. et al. Family unit surroundings and development in children adopted from institutionalized care. Pediatr Res (2021). https://doi.org/x.1038/s41390-020-01325-1

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01325-1

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-020-01325-1

0 Response to "Adoptive Children Resemble Adoptive Family Through Enviormental Factors"

Post a Comment